About Carver Blanchard

Carver

Blanchard brings to modern audiences the sparkling tradition of

composition and arrangement for the lute that began in Renaissance

Europe.

In the spirit of the early English master John Dowland,

Blanchard has adapted spirituals, worksongs and other traditional music

of the American South for performance with this classic and intimate

instrument. By including new works of his own, he illuminates four

centuries of musical and cultural history.

Formerly lutenist to

the Smithsonian Institution, and tenor soloist in its early music

consort, Blanchard retains a strong interest in the Renaissance lute

repertoire and and always includes lively examples in his programs.

"Dowland and the other early masters were composer-arrangers to a man,"

he says. "What I am doing today is highly traditional."

Blanchard's

arrangements of 19th-century American music, usually from his native

South, provide a particularly engaging extension of this tradition.

Always audience favorites, they range from the rousing to the

sentimental, including lesser-know but haunting songs by Stephen Foster.

Carver

Blanchard teaches guitar and lute at Wesleyan University in Middletown,

Connecticut. He is artistic director of Carver's Barn, a small arts

center in Elka Park, New York, and lives in New York City.

________________________________________________________________________

Recordings ...

|

|

| Twelve Hymns - Click image for Song Listing and Samples |

|

|

|

| Click Image to Purchase This CD From iTunes |

|

|

Carver Blanchard's latest recording "Heartsongs and Audubon"

was recently released by Albany Records. Carver has divided this recording into three

sections. The first, Audubon, is a tone poem for solo lute by Blanchard

inspired by a poem of Robert Penn Warren by the same name. The second

section, Heartsongs, is a recreation of a late 19th-early 20th century

home musicale and the third is a group of hymns from the 1940 Episcopal

hymnal arranged by Blanchard for solo lute.

To order this CD please visit: http://www.albanyrecords.com/To Download "Heartsongs and Audubon" From iTunes

please visit: http://itunes.apple.com/us/album/carver-blanchard-heartsongs/id458216195

|

|

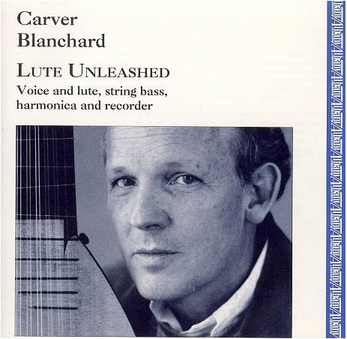

| Lute Unleashed - Click on this Image to Listen to Sound Clips in iTunes |

|

|

"Lute Unleashed

is a traditional recording in that it presents the work of a composer/

arranger whose instrument is the lute. In the foreground of most of the

works recorded here is Blanchard's voice and a very nice one it is.

Natural and unaffected, his voice helps the spirituals to sound with an

artlessness and immediacy that is important to the style."

~ The Guitar Review

|

|

| Five Premieres: Chamber Works With Guitar - Click on Image to Listen to Clips in iTunes |

|

|

Five Premieres - Carver Blanchard's Lament and Frolic, for flute and guitar is presented along with the works of four other composers.

|

“Lute Unleashed is a traditional recording,” says Carver Blanchard in his program notes to this CD, “in that it presents the work of a composer/arranger whose instrument is the lute”; however, as the somewhat tongue-in-cheek metaphor in the title implies, the whole concept of the recording is anything but traditional. Blanchard, a lutenist/guitarist/singer/composer/writer working in and around the New York area, has put together a most unusual and engaging collection of arrangements of music far removed both from the lute and the notions many of us have unconsciously developed about the instrument.

The music is divided into three categories: “Spirituals and Work-song,” “American Popular Classics” and “Music of Stephen Foster and his Era.” The stylistic variety points to the way Blanchard (and, as he argues in his program notes, every Renaissance lutenist) managed to develop a career---by taking advantage of whatever opportunities came his way.

Certainly, composer/musicians of the past worked in every available venue; and, while time has muted stylistic distinctions, one need only look at the somewhat unusual conglomeration of compositions of even so respected a classical composer as Haydin---with his works for baryton, hurdy-gurdy, etc., and his “occasional” works from dinner music to puppet shows to opera and church music---to see how accurate Blanchard’s observation is.

The arrangements (all by Blanchard) are generally well-conceived with regard to style, and they are fleshed out colorfully with first-rate performances by Nel Moore on harmonica. Glen Saunders on string bass, and Jim Cowdery on recorder. There is a variety in these performances as well, though all are similar in that each has a good musical “pedigree” while sharing a more “vernacular” perspective in the choice and use of instruments.

In the foreground of most of the works recorded here is Blanchard’s voice, and a very nice one it is. Natural and unaffected, his voice helps the spirituals to sound with an artlessness and immediacy that is important to the style, while his lute work, simple at first, gradually takes on a complexity that raises the style beyond its origins to a more intense and personal musicality. The opening song, Steal Away, is a case in point. Lute, voice and then harmonica and bass gradually coalesce into a simple but engaging introduction with a subtle, muted feeling that conveys the mingling of melancholy and hope implied by the text.

Look Over Yonder/Another Man Done Gone, picks up the intensity, first with the unaccompanied voice, then with instrumental strokes; then Blanchard, with Moore and Saunders, moves into a wailing southern blues bersion of Another Man, that can stand the hair up on the back of your neck. Blanchard’s southern drawl (he was born and raised in Louisiana) is perfect for the style. Only in the second set of songs (“American Popular Classics”) does Blanchard get a bit coy, his voice taking on, in songs like Night & Day and Begin the Beguine, the sound of a “song stylist” which is not as effective as the spirituals. But it’s all in fun at this point, and even I had to crack a smile at hearing a lute playing on the early Elvis Presley hit, My Baby Left Me. (I suppose Palestrina got much the same reaction when he wrote his Missa L’Homme Armé--- “Do you mean to say he’s using that beer-and-brawl pop song in church...”)

There are a number of non-vocal arrangements here as well. Irish Suite, featuring Jim Cowdery on recorder, is very effectively worked out, and Cowdery is wonderful with his subtly ornamented lines (given greater authority, no doubt, because of his doctorate in Irish Music!) The opening jig of the suite is a fast and energetic work in perpetual motion. Blanchard’s arrangement has the recorder playing non-stop divisions while the lute dances around it, sometimes in a startling unison, sometimes breaking off into parallelisms and more contrapuntal gestures. The middle ballad is more plaintive, with effective counterpoint for recorder and lute. Following this is a sort of strathspey/jig, again having long ornamented variations on the recorder with the lute interweaving an accompaniment, and occasionally rising to unison work. The arrangement throughout is tightly and ingeniously woven, and the combination of recorder and lute is both authentic and acoustically natural.

Suzanna’s Fancy, features, as one might expect, the harmonica, but it is neither precious nor precocious in sound here. Blanchard’s arrangement---as in the Irish Suite---is a true fantasia, highly developed with respect to both melody and tonal structure, and containing a full measure of lute counterpoint. Nel Moore on harmonica uses a straight-forward approach to sound and inflection, allowing the music---rather than any clichés in sound or articulation---to come to the fore. Once again, the effect is both natural and musically interesting.

Moore has an opportunity for greater range in Southern Suite, particularly in the second movement (Nobody Knows the Troubles I’ve Seen) where a sort of film score folksiness pervades. The suite opens, with both humor and intensity, on the tune, Turkey in the Straw, using banjo “fanfares” and imitative counterpoint. Wonderous Love, is given a full-blown Bluegrass banjo treatment, with a rich mixture of frailing and Travis-picking. While the combination of religious hymn with Bluegrass may seem unusual, the combination is actually indigenous to the style; and Blanchard, on solo lute, invests the music with great intensity and character. The suite closes with a vibrant and carefree spirit, in a rollicking improvisatory mix of lute, harmonica and, coming into its own, the string bass. Glen Saunders (who at the time of the recording was completing a doctoral program at the Manhattan School of Music) provides a stylish foundation throughout the recording and has a nice blues touch both in this last work and elsewhere.

The lute on this recording is an eight-course renaissance lute made by Robert Cooper. Its tine is not as deep or rich as others I have heard; on the other hand it has a fine transparency and clarity which Blanchard manipulates well. On this CD the lute serves as banjo, mandolin and rhythm guitar, and it is nice to know that an instrument so apparently restricted in repertory and style can be extended so effectively.

|

Tears and a Swoon for Carver Blanchard

By Cat Ballou

The house beverage is stand-your-spoon espresso on the Elka Park back porch of Louisiana born lutenist Carver Blanchard, picker and singer on the Albany Records release Lute Unleashed. Come autumn, when the leaves are down, you will see infinities to the Northeast only sensed in summer from this Catskill mountaintop plateau. It’s a home site to suit a hawk, or maybe that renegade “breed,” Brandt, who led Native American bands down the Platte Clove out of a camp not far from here to torch Woodstock during the Revolutionary War. Also, it’s a spot eminently suited to an artist who grew up adjacent the boundless horizon of the gulf and the rolling Big Muddy, immersed in the jambalaya of musical influences in New Orleans---cajun, zydeco, classic European and old American South---accustomed to absorbing it all, without any sense of boundary.

Blanchard who retains a Manhattan apartment and teaches lute and classical guitar at Wesleyan, says he came across his Elka Park place by accident-->

It was at one such production last July that Blanchard unleashed the Orphic touch, arresting our attention. Seated in a camp chair under a white fedora, a fit aristocratic cross of Truman Capote and Hunter Thompson, playing old American tunes slightly miked to carry through the great outdoors, the spring and sing in his lute lines pricked the heart, softening it for the play’s dramatic kill. The actors’ denouncement in Death of the Old Man temporarily turned July’s perspiration to tears, but who, we had to find out, was this picking pied piper of a side man?

After a chase across the grounds the courtly Blanchard presented us with his Lute Unleashed disc, including “spirituals and work songs, American popular classics and music of Stephen Foster and his era.” Liner notes say he is joined on the CD by a master bass man out of Julliard, Glen Saunders, Doctor Jim Cowdery from the ethnomusicology department of Wesleyan, and Nel Moore, a University of South Carolina graduate, on harmonica. Then we trip down to a mountain studio, secret as Brandt’s lair, to savor the prize. Here, where the sound-proofing carpet is three inches deep, conducive to silent dance, the engineered sonics are state-of-the-art and the beer is crackling cold, we enter Blanchard’s musical world like Jonah in the whale’s belly, consumed with joy, sorrow and ultimately awe.This all transpires from the first cut, “Steal Away.”

Who says white men can’t swing? There’s a big, easy pulse to the tempo Blanchard and Saunders hit that embraces and rocks, while Blanchard sings along in an absolutely true tenor, transparent with hope, sincerity and innocence. New Orleans bootleggers could distill from the well-spring of this man’s voice and run the clearest whiskey ever. “Another Man Done Gone” carries as a poignant lament, while “Go Down, Moses” tumbles out in a fervor of affirmation. The classic, immaculate, soul-sent picking behind Blanchard’s arrangements of these work songs and spirituals, sung with the gentle inflection of his Louisiana accent and rising from an open heart, make them authentically his own and still universal in their wonderful disturbance.

Witness the been-there, heard-that Woodstock studio musicians who drifted into the listening room, afflicted by the sheer yearning and purity of Blanchard’s songs. One by one, these heavy-metal men picked up acoustic instruments, touched wisps of fiddle, picked guitar riffs along with the lute, hummed a descant. A full trio behind Blanchard’s plea of Steven Foster’s “Hard Times, Come Again No More” turned into retro-church choir boys hungering for a connection to the harmony in this music that has nothing to do with notes. Who would think seven minutes of Cole Porter’s “Begin the Beguine” set among an uptempo groove of gospel and blues man Arthur Neal Gunter’s “Baby Let’s Play House” and Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup’s “My Baby Left Me” would hang like smoke, a fragile and sensual reverie set to the echo of a cha-cha-cha dance pulse, inducing tears and a swoon at the same time.

Blanchard’s collaboration with Cowdery piping on recorder in “Irish Suite” (arranged by the lutenist) has a classic brilliance and Celtic wilderness. Artists, composers and institutions---Richard Dyer Bennet, Bernard Krainis, the Guitar Society of America---have all celebrated the classic side of Blanchard’s performance and compositional achievements. However, what drew us, cat-curious, to his back porch for an interview is his uniqueness as a one-man renaissance of Southern gentlefolk songs, soul-fired and classically meticulous.

Carver says music was always there for him, like Gulf Coast humidity. His father was a choir master, though he quit before his son was old enough to join. When the family moved to New Orleans from Baton Rouge, the boys who grew up to be the Neville Brothers were the house band for his neighborhood bar.

“I never had any intention of becoming a musician,” he reflects. “I was a tennis player and went to Northwestern University on a full tennis scholarship. Then I heard my sister got a scholarship to Oberlin, and it took me about five minutes to decide I was going to be a musician. It was radical, but the dean of the music department let me in.

Blanchard’s instrument was classic guitar, which he continued to study at the Peabody Institute with Aaron Shearer, when the draft was about to take him during the Vietnam War. He auditioned as a musician for three branches of the service, was accepted by every one, and ended up singing tenor for four years with the Air Force’s Singing Sargeants. Based mainly in Washington, D.C., during this period, he was subsequently drawn into performances in the Washington Consort, associated with the Smithsonian Institute, where he finally picked up the lute, his instrument of destiny, or one of them, anyhow. In addition to his association at Wesleyan, Blanchard has performed and recorded classic repertoire of guitar and lute; his professional collaborations involve work with soprano Julianne Baird and the Crofut Consort.

We perceive all this as preparation for great musical deeds to come. This fall, when the Greene County highway department temporarily closes the Kaaterskill gap, Blanchard will have to trip down the mountain along Brandt’s old run through Platte Clove. This man has his own fire to bring to Woodstock, the eternal flame of an American folk art, and he will find some peers in this town, fiddler Jay Ungar of “Ashokan Farewell” fame, and Dennis Yerry, playing a fusion of jazz and Native American music, among them. Both these artists have lit the nation with similarly unique ethnic-classic folk musics, and we expect the country will catch up with Carver Blanchard’s contribution as soon as word gets out.

Catskill Mountain Guide Magazine

Carver Blanchard, Lutenist

By Ann Hutton

We made an appointment to meet at a coffee bar on Wall Street in Kingston, not exactly in between the Connecticut recording studio where he’s currently working and his home in Greene County, but close enough. When he slid into an empty parking space right out front of Hudson Coffee Traders on a street that never offers a break and doffed a Panama hat, fairly bouncing out of the cold and into the building, I guessed that this Louisiana native might carry his own sunny disposition with him. Anyone who wears straw in the frigid gloom of an upstate December must be able to create his own heat and light. Indeed, Carver Blanchard appears to run on stored positive energy. Could it be a life of plucking a lute—an almost ancient instrument associated with simpler times—that causes this inner reserve of warmth?

It's not a simple instrument to manage, ubiquitous as it was in the 17th century. With eighteen courses it has a huge range, but all those strings can be temperamental. Blanchard explains that a lutenist would have originally been employed as a studio musician might be today, to provide functional background accompaniment for events at court, for example. Players would be expected to maintain a large repertoire and be able to improvise on demand. He imagines an entire industry built around the production of lute bodies and parts, and emphasizes the expertise required of even the string makers of that era. When the harpsichord was invented, it and the Baroque violin became the dominant sounds, and the lute literally dropped out of hearing for a few hundred years.

Its revival has come about almost incidentally. Blanchard, like most modern lutenists, did not pick up the instrument as a first choice. The lute is not taught in elementary schools, nor is it yet commonly heard on the radio. Furthermore, lutes are not widely made and distributed. Blanchard’s instruments come from an artisan in Savannah, GA. Although there exists a handful of lute makers in the United States, as well as numerous lute societies, the market is not what it was in Renaissance Europe, if such a comparison can be made. Each instrument has to be hand-built, and modern lute makers are unable to charge what their labor is actually worth in terms of time and skill.

Still, Blanchard envisions a growing interest in the lute’s possibilities, attracting the creative talent that could bring it back as a standard instrument within the modern entertainment industry. To that end his CD, Lute Unleashed, released in 1993 by Albany Records, introduces the lute as part of a more contemporary quartet featuring Neil Moore on harmonica, Glen Sounders on double bass and Jim Cowdery on recorder. With selections by the likes of Stephen Foster and Cole Porter (and including a couple composed by Blanchard himself), Lute Unleashed offers the listener an alternative genre for the instrument’s unique qualities. He maintains, “The instrument is good for a variety of musical styles, even more contemporary ‘prop’ music. There are things it will do that a guitar can’t … and it sounds like a classy banjo when you do [traditional] American music."

Blanchard came to the lute almost accidentally. As a guitarist and a tenor in the Air Force’s performance group “The Singing Sergeants,” his musical interests leaned towards the arrangement and composition end of the field. He joined the Smithsonian Institute’s music department as a singer; and when the lutenist left, there was a space to be filled. He became a lute demonstrator for the Smithsonian—and his relationship with the instrument took off. In addition to composing, arranging and performing, he is the director of the Fernwood Center for the Performing Arts in Elka Park, NY, and he teaches at Wesleyan University. His students there almost all start with the guitar and migrate to the lute. He says the kids can bring anything to him—like ‘60s era music from that fantastic explosion of talent—and he’ll figure it out for them.

He yearns for a critical mass of players and listeners who will revive the public’s appreciation of the lute and create new music. In fact, Blanchard dreams of developing his property in Elka Park—once the Poggenburg estate near Tannersville—to house an arts academy, a place for musicians and writers to hone their talents while taking advantage of the peace and beauty of the Catskills. He points out that Tanglewood in the nearby Berkshires was an outgrowth of just such an academy, and that all it takes to accomplish is the support of the surrounding communities—support like “Mrs. Vanderbilt getting all her dinner guests to pull out their checkbooks to make things happen,” he adds, his eyes twinkling. Anything could happen. I’m ready to sign on.

Blanchard’s current recording efforts entail three microphones bleeding sound into each other as he plays and sings solo—quite different than laying down separate tracks with three other musicians, with a sound engineer manically listening to every incremental vacillation in tone. He’s recording in a vast multi-purpose room at Wesleyan that looks like a mock-up of a classic ‘50s studio, and his choice of music centers on turn-of-the-last-century stuff his grandmother had in her library. One of the challenges is to avoid sentimental, antiquated renditions of these old tunes. “…like ‘Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes’ not sung as a period piece, rather as serious lyrics … you want to mean it but not over-sing it. What you want [to achieve] is transcendence. Not to be noticed for your technique, but for the music itself.” Hailing from Baton Rouge and New Orleans, he says this kind of music has stayed with him, but then jokes, “I’m looking forward to finishing up with this effete stuff and getting back to some rock and roll!”

With background strains of Foster’s “Hard Times Come Again No More” from Lute Unleashed competing against customers’ chatter, a noisy coffee grinder, and the clink of cups, Blanchard points up at a speaker and interjects “The ear accepts a variety of phonic balances—and that’s the way people listen! Or like the secretaries listening [to music] very low and around the corner.” He says if it isn’t interesting to hear in different settings, it won’t grab your attention anyway. He maintains that for any creative artist, there is a certain level of dedication which, once achieved, the world comes to your assistance. When your commitment to the art itself—be it playing the lute or writing a play or whatever—is strong enough to “throw away the safety net,” the muses will know it. Blanchard admits his modest success allows him to experiment, but he can’t get away with just anything. "At least people know I’m serious … If you’re good enough for long enough, the world will notice. But, do not underestimate how good for how long you have to be."

He’s been good for a long time. Look for Carver Blanchard’s new Albany Records CD, titled Heartsongs and Audubon, to be released this spring.

|

"If music be the food of love, play on. Give me excess of it; that surfeiting, the appetite may sicken, and so die." - William Shakespeare

|

|

|